This is a story common to all women in varying degrees of similitude, but a particular little girl enjoys the limelight in mine because she had a painting to look at. It was a painting her mother had painted, which her father also looked at. Though it was not often that she got a glance at it, anybody else hardly ever did.

This was not the only painting her mother had painted. There were many, most of which were painted during the mother’s maiden days. Her paintings had been valued as mere decorative pieces to complement the furniture in her maiden house, she felt, so she folded them up and took them to the new house when she got married. The new house already had some decorative pieces to complement the furniture, so the paintings were folded up and kept away in the store room.

Once a year, they were taken out, only to be cleaned up and put back again. One such odd day on one odd occasion, the little girl caught sight of that painting. As her mother sat dusting it with a piece of cloth, her eyes followed her mother’s hands tracing the shapes with clean, wet strokes, and she gazed at it from behind her mother’s shoulder.

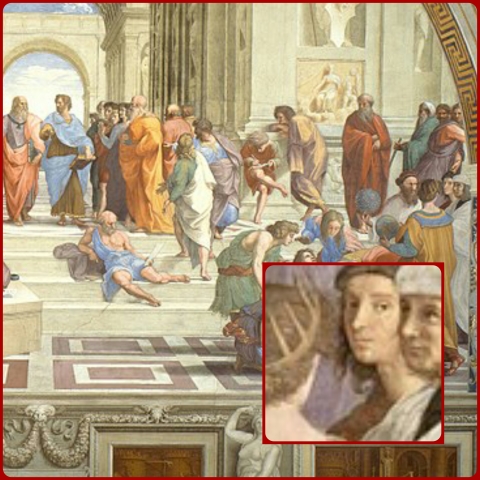

She had a better look afterwards. There was a sylvan setting, nothing short of a dreamscape, with heavy flower-speckled foliage and butterflies fluttering above. Amidst it were three women with flowing robes tied loosely around their petite curves and patches of flowers tucked in their hair here and there. They were involved among themselves, busy in their passive plays by the waterside, and a light chatter flowed through the scene, it seemed. They were not painted to perfection, but they were beautiful.

There were several others—a portrait of bani-thani, one of a sringarika, some floral still lives, and a few landscapes—in the lot but that one had an unrivalled appeal for her.

By the time her father came home, she had selected the wall which was good enough to be graced by it, had decided to remove the wall-clock to clear the spot for it, and had fancied complementing curtains in the background to go with it. She fancied the painting in the limelight of everyone’s gaze, and thought of the appreciation it would earn its artist. Excited, she rushed to the father and announced her plans to him.

“Which painting?”

“Oh,” she dragged her father to the large canvas, unrolled the heavy sheet and pointed to it, “this one.”

Her father instantly gave a confused, unimpressed look which subsequently turned into a frown. He raised an eyebrow, shook his head, and told her to choose some other painting.

“Such a painting belongs in the bedroom,” he said. He looked at it for a good two minutes before busying himself in other work. The little girl could not understand what he meant but did not like the idea at all. Yet she knew her father’s judgement was final and binding—it was always final, whatever he said—so she started considering another painting which might be good enough as a replacement.

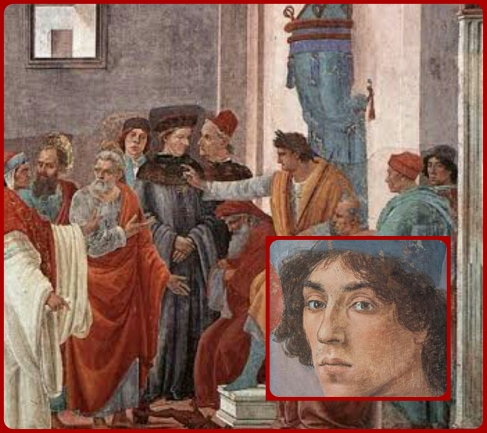

She chose the bani-thani and her mother said that she found the sringarika pretty. The father thought them appropriate enough to be exhibited; his gaze approved of their aspects. They were beautiful, undoubtedly, but she found it unsettling what had made the father approve of them and dismiss the first one. The two portraits depicted women thoroughly adorned with specks of alta, veiled in gold-inlaced drapes, and wound in coils of pearls. Pearls after pearls in coils after coils were painted as perfect rounds, kept apart at measured distances, never touching the next pearl yet seemingly stringed together by the sheer force of discipline. The women stood far removed from any discernible background. They stood perfectly still. They stood perpetually silent. They stood only to be looked at.

Then there were The Three Women who were always too busy frolicking among themselves to acknowledge any gaze that the father had been trying to protect them from. She could not look at them very often but she heard their chatter, distant and unintelligible, whenever her mind wandered off to them. Quieting them at intervals, she could also hear her father’s words about “such a painting”, “such a girl”, and such others.

Their chatter and those words rang together in jumbled dissonance until they turned into an incessant babble, a constant disturbance. As the babble started making sense to her, the disturbance deepened; she came to understand why that canvas was folded up and kept away in the store, why the bedroom was otherwise the only safe place to keep those women, why their bare skin was made unavailable for the gaze that relished it; she came to understand why her mother had not wished to exhibit her own paintings all these years, why her father had more say in how and where those paintings were to be exhibited, why everything her father said was final and binding; she understood that her father had looked at the painting for a good two minutes before dismissing it as inappropriate.

The babble still keeps ringing but now she can decipher distinct notes of the disturbance. The painting still sits folded away but now she sees it in shades and tones of understanding.

Written by Eshna Gupta

Edited by Shriya Kotta

Images provided by Eshna Gupta