Google served me with the expected lot of artworks when I looked up artworks from conflict zones, fascist regimes, and episodes of impending war—those which criticised wars, mourned innocent blood, expressed pathos, inspired pity. Soon after, I was served with the unexpected when the web search brought me to a realisation that in conflict zones, fascist regimes, and episodes of impending war, the art that flourishes is but an attack on those factors.

It was not the grey drawings of humans and animals devastated by this world’s violence in the Guernica, neither the disintegrated canine faces in The Wolves that Franz Marc painted amidst the violence preceding World War I, nor the poignantly horrifying blank stare—the ‘two thousand yard stare’—of an emotionally defeated war soldier, which worked its intended influence at that time. Far more influential were posters convincing people that feeling a certain way, taking certain decisions and believing what they are being told is best for them and their country. There were posters from the World Wars telling people that serving in the army is the best they can do in their lives, picture of Rosie the Riveter from America during World War II telling women to become ‘strong and capable’ by manufacturing war weapons, a poster counting casualties of the Bataan Wars in the Philippines and calling Filipinos to ‘stay on the job’ until every Japanese ‘is wiped out’, a North Korean poster for school children to take up respectable professions which can contribute towards killing Americans, are only a few examples.

The Guernica, now famous as an icon of anti-war art, was then displayed only in fancy galleries of the globe where few people could visit it and even fewer could have taken it to heart. The common people, who needed this anti-war impetus, could not access it let alone be influenced by it. The posters, however, were published to occupy all the public spaces frequented by people and obviously had more power over their minds.

Reflecting on my own times and trying to establish a pattern, I wonder if there is any painting in some fancy art gallery of my own city, which can powerfully tell people to stop killing other people but will do so only after it’s too late. I close my eyes to imagine what that painting might look like, but as soon as I open my eyes, I see instead a movie advertisement on a huge hoarding. The poster keeps changing, sometimes lauding a powerful leader to make him more powerful, sometimes boasting about the nation’s ability to kill, sometimes celebrating our hatred for the neighbouring country, or sometimes rhyming along hate speech directed at our own people. These days, it is always a movie poster I see and it is always lecturing people what sentiments they should have and what opinions they should not have about their country. I see those promotional posters every day and I think of people who saw the other propaganda posters in the same way; the huge boarding blocks my view as well as the sunlight which used to fall on my window and I understand how people living during wars are persuaded to live under blinding darkness.

Yet, when I think of artists during disturbed times, I innately think of them as more enlightened than their people, thinking of only those guided by conscience not commission. My mind conjures an image of an artist working in the quietness of her room with the utmost calmness that boosts the precision of her skills. I think more about her calm and precision such that she stands out against the clamour and chaos of that reality outside of her room. I imagine a moment when the growing disturbance outside interrupts her process and her distress over the state of affairs distracts her; yet, at large, the distress is what drives her. So, for the moment, she shuts her windows to keep the noise out and gets back to her silent rebellion, and sunlight filters in through the glass panes, though blunted by clouds of dust. That is how I imagine Guernica and the like of it were made.

But I actually see artists of my time raising their voices to join the cries of trouble-makers, bringing out high-end audio equipment from their recording rooms to add to the cacophony of loudspeakers on the streets. I encounter puppet shows where glamorous puppets perform and propagandists stand ventriloquizing the scripts from behind. I see them play it out in dark, packed rooms where people not only get trapped willingly but also celebrate their shackles by stirring up a bedlam of claps and cheers from time to time. Every time I see my surroundings transforming into one of those rooms, and the noise becomes unbearable, I quietly wish there exists another room—where the noise is shut out but sunlight filters through the window panes, though blunted by clouds of dust. I wonder where that room is, I wonder about the artist who is working to create her individual rebellion amidst the disturbing forces, and I wonder how much at loss with the state of affairs she also feels; but I also wonder if she has suffered any loss in the state of affairs, I wonder if she has been troubled enough in the safety of her privileged room, and I wonder if her rebellion would speak up only after it’s too late.

Written by Eshna Gupta

Edited by Shriya Kotta

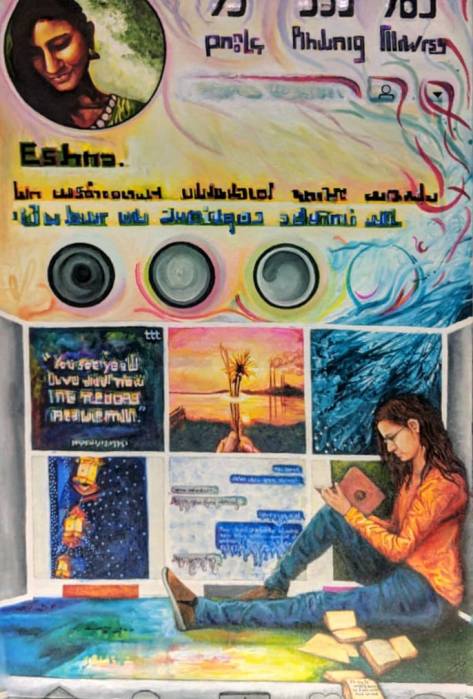

Featured Image is a crop from a propaganga poster from 1942