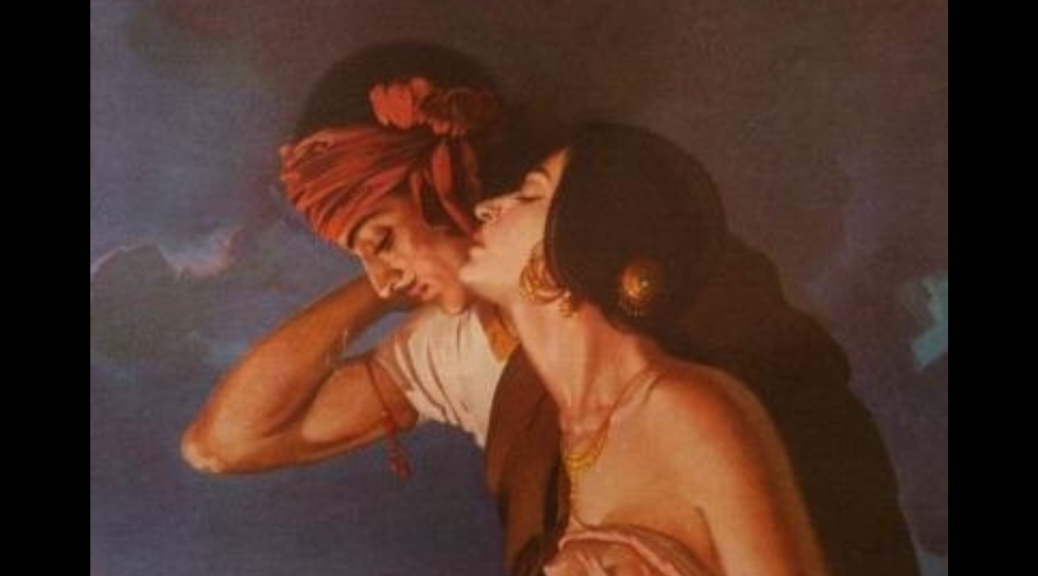

Almost everyone has heard of Mirza-Sahiban and Heer-Ranjha’s eternal tales of love. However, a lesser-known but equally poignant story from Punjabi folklore is that of Sohni-Mahiwal, also called Suhni-Meher. Set in 18th century Punjab, the story is about two lovers – a potter woman called Sohni and a prince turned herder called Mahiwal. Part of the oral folk tradition, the tale has featured in the written form as part of Shah Jo Risalo – a poetic compendium of a Sindhi Sufi poet, Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai.

Sohni, born to a potter father, helped him make pots on which she engraved beautiful designs. They resided along the river Chenab. Shahzada Izzat Baig, a rich trader from Bukhara (Uzbekistan), came to Punjab for some business work. There, he saw Sohni at the pottery shop and got enamoured by her beauty. Consequently, he started to visit her every day under the pretense of buying pitchers. Their love for each other gradually developed and deepened to such an extent that Baig did not return to Bukhara and took up the job of a herder called Mahiwal at Sohni’s house.

As soon as Sohni’s family discovered their tryst, they instantly got her married to a fellow potter owing to hesitations based on class difference. This devastated Mahiwal who then moved to the other side of Chenab and became a fakir (saint). However, the married Sohni defied all odds and swam across the Chenab every day to meet Mahiwal on the other side. There, by the riverside, he caught fish for her which she relished on end. However, one fine day, when Mahiwal was unable to catch fish for her, he cut the flesh from his thighs, roasted it, and gave it to her to eat. Unaware that the meat was her lover’s flesh, Sohni savoured every bit of his thigh. Moreover, she went on to remark that his flesh was the tastiest meat she had ever tasted. This! This is the metaphor that has sadly not been taken up by a lot of critics. Her consumption of her lover’s flesh and general obsession with meat are covert metaphors for passionate and lustful love.

Undoubtedly, there is a strong symbolism for lust and passion vis a vis meat-eating. It’s said that Sohni was very fond of eating a particular kind of fish called mahseer (carp). So strong was her addiction to mahseer that Mahiwal had no choice other than giving her his thigh flesh when he couldn’t find any fish meat. Notably, this ‘meat obsession’ in storytelling goes back to the times of Baba Sheikh Farid- another 12th-century Sufi poet from Punjab. In a couplet, Baba Farid wrote about his extreme desire to watch God with his own eyes. To achieve the same, he allowed a crow to eat his entire body, save for his eyes. Indeed, the crow can be deemed an embodiment of the five vices that Sikhism recognises: kaam (lust), krodh (rage), lobh (greed), moh (attachment), and hankaar (ego). Similarly, Sohni eating her lover’s meat signifies this kind of extreme passion wherein eating her lover’s flesh is her way of expressing her desire to savour every bit of his body and soul. It’s almost as if Sohni wants one part of Mahiwal’s body to reside in her own self. Generally, the smell and texture of meats are supposed to be very tempting. Even biologically, thighs have softer flesh than other body parts. Consequently, the act of chewing a soft tender piece of body flesh has explicit sexual and aphrodisiac connotations. The tenderness of the meat is metaphorically juxtaposed with the tenderness of their love.

One may ask why Mahiwal’s meat tasted better than the fish’s to Sohni. The answer lies in the ideas of sexual appetite and gluttony. Understandably, communicating a married woman’s extra-marital sex life in old-world Punjab wouldn’t have been a cakewalk. Thus, what might appear as cannibalism on Sohni’s part to present day observers could very well be a euphemistic reference to intercourse and the ‘union’ between the bodies of Sohni and Mahiwal. And maybe that’s why the human meat’s flavour surpassed that of the fish’s meat – enhancing the former was the tinge of sexual intimacy.

This covert female sexual agency in a Punjabi folk tale is not surprising. Punjabi folk tales are known to be daringly feministic in their approach. Like all Punjabi love sagas, this story’s title, too, has a woman’s name first (Sohni). Furthermore, many old-world societal notions decree eating meat to be a more masculine activity; one needs male ‘courage’ to eat an animal. In Sohni-Mahiwal’s story, Sohni’s ‘gentle cannibalism’ subverts 18th-century ideas of masculinity. Along with her beloved’s meat, Sohni also ‘eats’ up the period’s imposed patriarchy and male dominance. Interestingly, meat was considered a ‘high-status’ food in erstwhile Punjab. In view of the same, Sohni’s consumption of the ‘soft skin’ of a prince turned herder can also be a metaphor for her repressed desire to belong to a higher class.

In contemporary times, Bhaskar Hazarika’s 2019 Assamese directorial, Aamis has explored the tale’s ideas of cannibalism and lust. The movie, seemingly borrowing its crux from Sohni-Mahiwal’s tale, depicts a kind of sexual cannibalism called ‘vorarephilia’ – a paraphilia in which individuals are sexually aroused by the idea of being eaten, eating others, or fantasising about the two acts. It relates the strange love between Sumon – a young Ph.D. scholar exploring the meat-eating tradition in North East India, and an older woman called Nirmali. Their love story, like that of Sohni-Mahiwal, is dominated by their mutual gluttonous love for meat – animalistic or human. Their uncontrollable lust for each other and flesh culminates in Sumon murdering someone and giving Nirmali a large chunk of the dead body’s flesh to eat. Both Aamis and Sohni-Mahiwal’s tale deviate from mainstream romantic stories and explore ‘forbidden’ love masterfully.

A contemporary and technical term like cannibalism does not suffice to explain Sohni-Mahiwal’s extraordinary love story. The act of meat-eating is a clever and passionate folk metaphor for sexual intimacy. All in all, it is the subversion of platonic, courtly, and ‘genteel’ love, characteristic of most other Punjabi folk love tales, that makes Sohni-Mahiwal a tale for the ages.

Written by Navneet Kaur

Edited by Tarini Gandhiok

Featured image via WorthPoint

are there different strengths of cbd cream

LikeLike